Substitute teacher shortage plagues Norrix staff

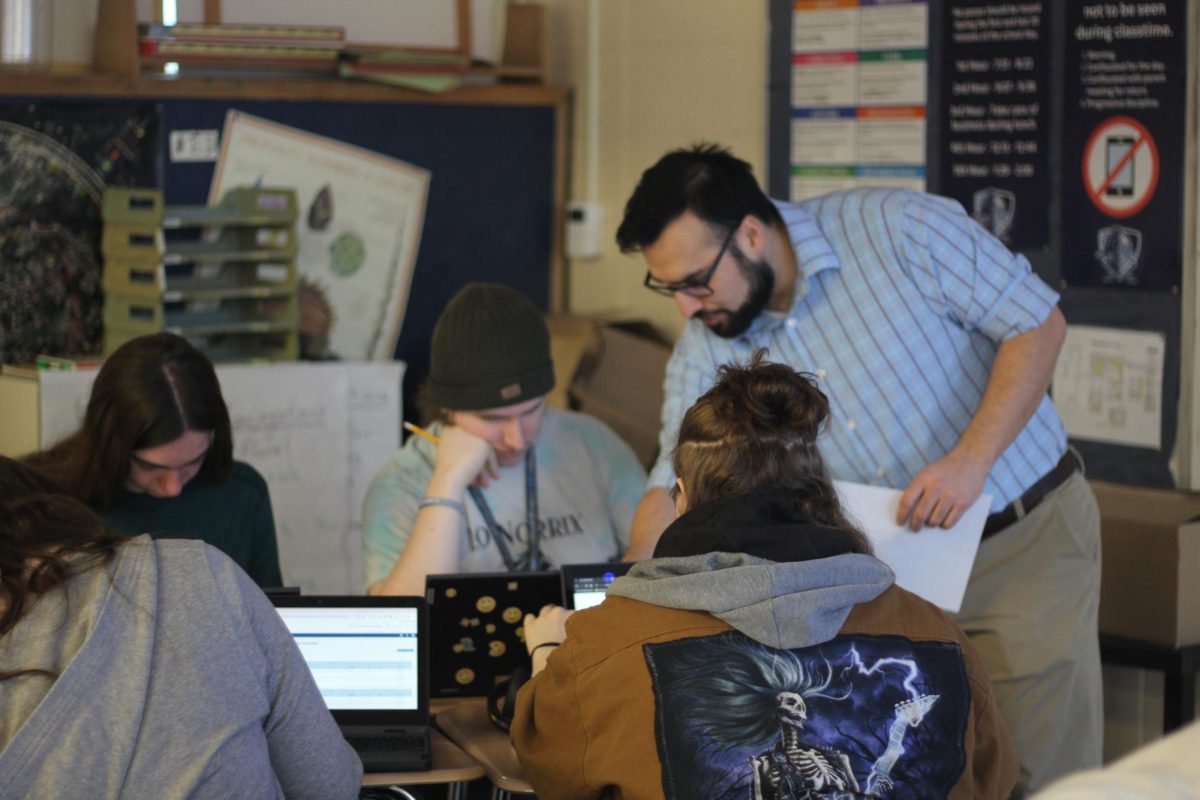

Credit: Elliot Russell

Spanish teacher Marta Grabowski substitute teaches for Atiba Ward’s fifth hour international business class. Like all teachers at Norrix, she’s been called in to sub on a rolling basis.

November 10, 2021

With teachers frequently in and out of the building because of COVID scares as the pandemic rages on, familiar faces have been popping up around the building. Maybe your algebra teacher had to lecture your world history class on the Ottoman Empire, or your chemistry teacher was made to read aloud a passage from “Beowulf” to your English 11 class. Whatever it may be, one of your teachers has reluctantly stood in for a colleague and given up their planning period, a time set aside each day for teachers to prepare instruction and assess student work, at some point or another.

Across the U.S. school districts are suffering from a drought of substitute teachers. Coming off of the pandemic, there are still a number of reasons for workers to stay home and out of the workforce. Whether it’s the fear of contracting COVID or dissatisfaction with the daily work routine, a record number of job openings have been posted in recent months following the end of last school year. The issue has been visible in the form of hiring signs outside of restaurants and stores everywhere, but it took the beginning of the school year to reveal the more serious implications this would hold in education.

The situation in Kalamazoo Public Schools is no different. Understaffing has been prevalent in nearly every part of the district: bus drivers, campus safety officers, teachers and, of course, substitute teachers. These times have called for drastic measures, which in the case of the sub crisis has meant falling back on teachers, or sometimes even principals and guidance counselors, to act as substitutes whenever the few remaining dedicated substitutes are occupied. This means teachers are forced to sacrifice their one-hour planning period whenever they’re called in.

“In the morning when I wake up at about five, I check that [teacher absence reporting software] to see what teachers are out,” said assistant principal Andrew Muysenberg, who has been overseeing the issue. “Then I have a spreadsheet that I use based on teachers’ plan periods, one through five, and I put them in alphabetical order. Teacher that’s up, it’s their turn to sub. Each teacher has the ability to pass once per trimester, so if they decide that day is not good for them, they can pass. They just know that they’ll be next up in line. Once they sub, they go down to the bottom and then we just rotate through. If we do have subs, obviously, subs sub instead of a teacher, but with the sub shortage, teachers are having to sub a lot on their plan time.”

Spanish teacher Marta Grabowski has felt the weight of this additional load. This year, being her first to teach in-person classes in the district, has posed a challenge as she tries to acclimate in these unusual times.

“So usually, as everyone knows, teachers have one period where they plan and instead, we’re having to go sub for other teachers because there’s just a global, I guess, lack of or shortage of subs everywhere,” Grabowski said. “So it’s this: the plan period for most teachers, and I know I speak for myself here, is like where I get everything together for the next day I can relax. I just take a deep breath. I could put grades in, I can respond to emails, because, I mean, you see how teachers are all day. It’s running from this side, helping this person, grading this, grading that, so that one hour dedicated to solely planning is essential for our job.”

Grabowski is not alone in feeling this way. The Kalamazoo Education Association, the local teachers’ union, has been pushing KPS to further address the issue. While article 22 of the KEA contract with the district states that teachers must sub once all other options have fallen through, they’re not satisfied with this as a long-term solution.

“A lot of times, though, as union reps, we don’t just solve things that are direct contract violations, but also the concerns of the people in our building in terms of making the building about a place for teachers and therefore also for students,” said teacher and KEA building representative Brianna English. “So the sub crisis is important to us because our planning time, which is guaranteed by our contract, is being taken away more frequently this year than it ever has before and we want that solved. We want the district to take measures to alleviate it as best as they can, so we’ve been pushing to make proactive steps to get more subs in the building.”

To actually get more subs in the building, the KEA proposes that the district raise its salary for substitute teachers. Currently, they’re paid $85 for a five-period day of work, or $105 if they commit to subbing in a single building, with two additional $100 bonuses for every ten days subbed in a given month. This pales in comparison to the $22.94 per hour curriculum rate teachers are paid for subbing, totalling to approximately $130 if they were to sub for a full day. To compromise, the LN KEA union representatives suggest a $125 per day wage for substitute teachers, with an additional $25 bonus for Mondays and Fridays and a $200 bonus for subbing every single day of a week.

“It shouldn’t be a financial burden on the district because they’re already paying us to do so,” English said.

Knight Life reached out to the KPS Human Resources department for comment, but did not receive a response.

Though neither of them are in the career for the money, long-time substitute teachers Bill Fette and Tamerah Mboup support the idea of a district-wide pay raise. Fette, who considers his time subbing in KPS since he retired from law in 2012 “the best thing’s ever happened to me,” even explored other options.

“Well, I’m getting recruited by all these different districts around, a lot of—most of them—pay more than Kalamazoo. That’s one of the problems with Kalamazoo. It’s more challenging in a certain way because we’re a very diverse system here and they don’t get paid very well,” Fette said. “Even before the pandemic, I know that we were having trouble getting subs in. I remember going down I-94 and seeing Paw Paw High School’s looking for subs.”

Paw Paw Public Schools, like many other districts in Kalamazoo county, are offering $110 a day to subs: an additional day’s worth of pay every week and then some. Saginaw Public Schools recently raised their wages to $150 per day for daily subs and $200 per day for long-term subs, who stand in for a teacher yearlong and write their own curriculum. Leveling the playing field with what regular teachers make to sub on their plan, Saginaw serves as a model for curriculum rate pay.

Fette also proposed the idea of the district allowing recently retired teachers to return as substitutes, which currently would threaten retirement plans under a Michigan state law put into place in 2010. This policy limits retirees’ earnings to one-third of their final average compensation if they return to work in a school district after retirement, majorly disincentivizing the practice.

“I understand that the state legislature has said that if you’re a retired teacher, you can’t come back and sub right away,” Fette continued, “and I think that’s crazy because they need subs, any people that understand the school system and are dedicated to public education, and yet they’re saying it’s going to affect your retirement if you go back and start subbing and it just makes no sense.”

With a great deal of experience under her belt, Mboup addressed the factors other than pay that could discourage potential subs.

“Whether you’re vaccinated or not, it’s not even an issue: you can still get COVID,” Mboup said. “There are people who have not had it. They don’t want to risk that and especially when myself, I have had it and I was very ill, so I don’t want to get it again, so it’s a little nervous for me every time I do step into a room and students, again, don’t want to follow the rules and pull their masks up or get angry that you’re asking when they know, that’s the rule to even come to school.”

“That’s unsettling to me because you’re playing with other people’s lives as well as your own, so it’s serious,” Mboup continued. “Me not being in my home affects my kids, so just coming in here to teach or to, you know, fill in for someone else is not worth that when students won’t do at least the measures they are supposed to do.”

Those who have done their time in the public school system can recognize how students’ attitudes toward substitute teachers differ from those toward regular teachers. It’s this elevated disrespect that concerns Mboup about the job going forward.

“If there’s no consequences behind that behavior, which I don’t know why they have the behavior anyway, then I don’t want to deal with toxicity,” said Mboup. “That’s toxicity towards a teacher there. No one wants to be in a working environment, a class environment where it’s toxic. When students are doing that, that becomes toxic and nothing’s worth that.”

If any light can be made of this crisis, it’s that both teachers and substitute teachers have been humanized. It’s expected of them to put students’ needs above their own; for that very reason, they ask for our respect.

“Just be kind to the substitutes that you have and like, non-teacher substitutes as well as the teachers who are subbing because it does place extra stress on us, and we are just trying to do our best,” said English. “Especially actual substitutes in the building. Be kind to them and treat them well because otherwise they may not come back and we really, really need them to come back.”

Mboup suggests that the district administrators meet with substitute teachers to address the ongoing issue. While the district and the KEA have already convened to work out solutions, the voices of actual subs are going unheard.

“What can we do as a district to support that so that we get the help and support we need from you because it’s a two-way street,” Mboup said.

Tamerah Mboup • Dec 8, 2021 at 9:33 am Knight Life Pick

Nice article. In reading this now, what particularly sticks out to me unfortunately is my comment on toxicity in the schools. Since this article we have had a number of violent threats here at Norrix as well as other schools in the district and fatal shootings at other schools. The depth of the toxicity & disrespectful behaviors that brews and goes unchecked leads to these unsettling and disastrous, tragic outcomes. Reading this now almost seems as if I was sounding the bells. Toxic environments cultivated by very disrespectful & harmful behavior that have no real consequences or deterrent actions have a negative downward spiraling effect on all whom is around it (students, staff & teachers). I just wish that as we all focus on budgets & planning we listen to the substitute teachers concerns and take them very serious and focus more on the health and well being of all the people to try to reduce the number of tragic outcomes. It breaks my heart when you have to fear for your life or the lives of any human being in a building of academia. This is the place you go to become elevated in society and engage in intellectual stimulation & growth. This should not be a place of fear. School is not a battlefield. My heart goes out to all of the recent victims and families of the recent shootings and lockdowns and unsettling uncertainties when you send your babies off to school.

Anise Strong-Morse • Nov 10, 2021 at 9:44 pm

Thank you for this really valuable and important reporting. You’re doing important student journalism.