Biodegradable pads and addressing menstrual poverty: Cecília Giacomin’s activism in Brazil

February 9, 2023

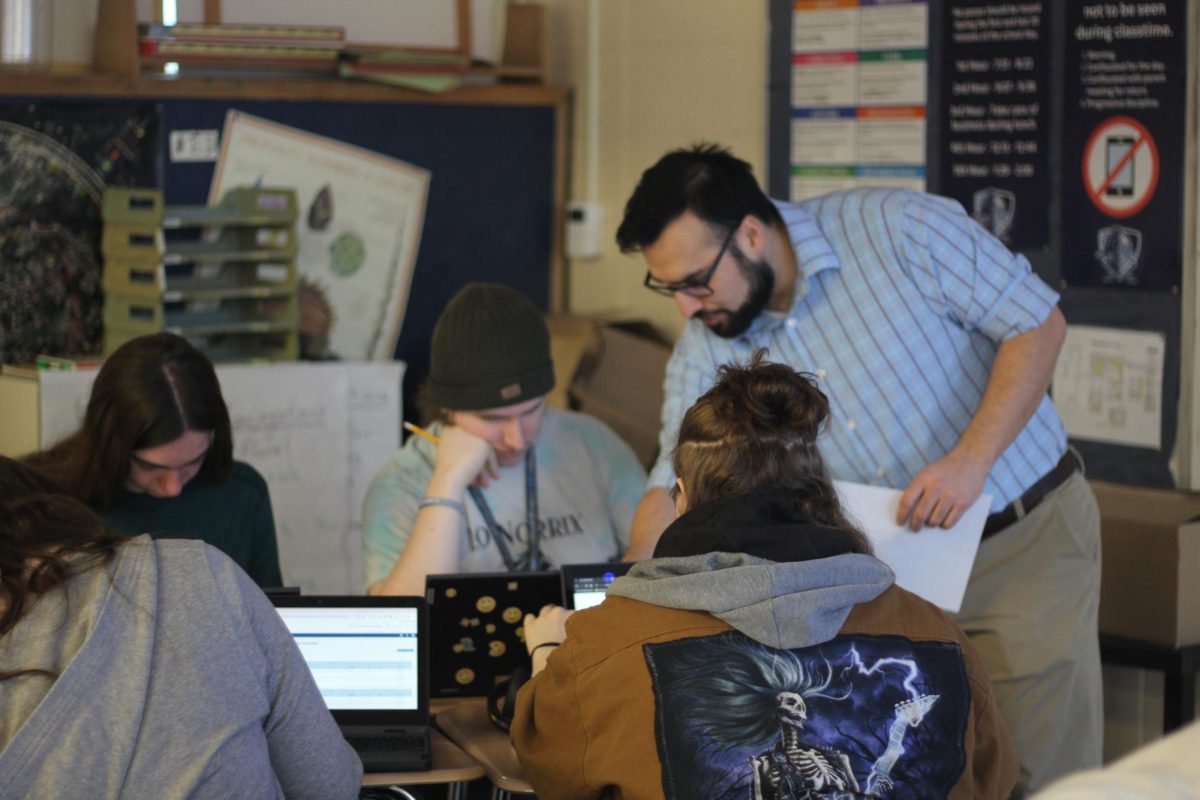

Editor’s note: This story is part of the Global Ties Kalamazoo and Knight Life Series. On Jan. 17 and Jan. 23 Global Ties Kalamazoo’s Youth Ambassador program from Brazil visited Knight Life. These stories are a result of the students’discussions with one another.

Making menstrual products affordable and eco-friendly is not a simple task in Brazil. Young activists, such as Cecília Giacomin, are working to make biodegradable sanitary products a reality. In addition to being environmentally safe, these pads would also be distributed free of cost to women in need.

Seventeen year old Cecília Giacomin traveled to the United States for a two week stay as a youth ambassador. In Brazil, she actively worked with Dignidade para Elas to create a biodegradable pad that’s 100% organic, as a part of her work to take steps towards gender equality in Brazil and help in aiding menstrual poverty.

An eye opening experience that sparked the beginning of Giacomin’s journey as an activist was hearing the story of a woman who had endured domestic violence. Since then, she’s dedicated herself to uplifting women around her and working to defend and promote women’s rights and equality in Brazil. We needed, together, to defend rights that, throughout history, were torn from us — Cecilia Giacomin

“I started talking about women’s rights and the struggle for equality when, for the first time, I heard the testimony of someone who for years suffered from such violence,” Giacomin recalled. “I was very young, and I remember feeling at that moment that nothing differentiated us, that we needed, together, to defend rights that, throughout history, were torn from us.”

Empathy, sensitivity and determination have been essential qualities for Giacomin to have as an activist. Being able to understand the struggles of women around her is one of the central influences on her activism work.

“It’s necessary to put oneself in the other’s shoes, see the situation as a whole and thus recognize that not all of us are leaving the same place. To start changing some scenario, or minimize any type of problem, you first need to know who the people affected are and how this problem finds them,” said Giacomin.

Along with other students from the Instituto Federal de Minas Gerais, Giacomin formed “Dignidade para Elas,” which translates to “Dignity for Them.” The main purpose of the project is highlighting and alleviating menstrual poverty in their community. One of the problems closely associated with menstrual poverty is the lack of clean and sustainable period products accessible to women. To start changing some scenario, or minimize any type of problem, you first need to know who the people affected are and how this problem finds them. — Cecília Giacomin

“It is estimated that a woman, during her fertile life, uses 10-15 thousand sanitary pads and produces approximately 4-5 kilos of waste per year,” Giacomin reported. “Because they are discarded after use, internal [tampons] and external pads are less economical and are very harmful to the environment.”

As Giacomin explains, the single-use nature of pads and tampons means that women around the world are paying thousands of dollars for hygiene products in their lifetimes. In the United States, this sum adds up to more than $5,000.

According to INTIMA and OnePoll’s survey in 2021, “the average woman surveyed spends $13.25 a month on menstrual products ‒ that’s $6,360 in an average woman’s reproductive lifetime.”

On top of their financial cost, period products are also devastating to the environment. According to Which Period Products Are Best for the Environment by Leah Rodriguez, “Pads and tampons go to landfills before they decompose into microplastics that pollute water sources like beaches, oceans, and rivers and contaminate the water supply that we drink.”

As Giacomin’s team started working towards engineering a prototype, they had to keep several factors in mind.

One of these factors is the uneven distribution of sanitary and well-maintained bathrooms for women in Brazil. Not having access to clean bathrooms leads to the spread of viruses and diseases.

Another problem was the differences between menstruating bodies. Not all menstruating people use tampons or are comfortable with using reusable internal products like menstrual cups. This meant that whatever product Giacomin and her team came up with, they would have to make it external and flexible to different body types.

Expense was yet another challenge. Many women in Brazil are unable to purchase the more expensive sustainable menstrual products. For comparison, in the United States, a 58-pack of unsustainable and non-biodegradable pads from Always costs about $6.29 at Target. A 56-pack of organic pads from Rael, however, costs $21.99 on Amazon. For this reason, Giacomin’s team is working to try and make their biodegradable pads completely free.

Despite these obstacles, Dignidade para Elas has produced a prototype of their pad. In addition to being biodegradable, the pad is 100% organic and disposable. They plan on distributing the pads free of cost through the Brazilian government, so that all women have access to them.

The journey to producing a prototype has not been easy. The team has been working in the laboratory since January 2022, with lots of research into the materials and chemical processes that make up both traditional and organic pads.

“The problem starts with the extraction of raw materials,” Giacomin explained. “Absorbent pads are mainly composed of cellulose and plastic, requiring oil exploration and the deforestation of trees for their manufacture. In Brazil, sanitary pads are not recycled and do not have a correct destination for disposal, which causes them to accumulate in dumps and landfills. In direct contact with the environment, these products release toxins and take about 100 years to decompose.”

To combat the disastrous environmental effects of discarded and unsustainable menstrual products, Dignidade para Elas is using raw soapstone as an absorbent for their pads instead of pure talc. Homemade glue, cellulose and glycerin — all biodegradable — were polymerized in order to form the plastic of the pad. Bamboo cloth was used for the top layer of the pad in order to avoid skin irritation.

Aside from working to make menstrual products sustainable, the team is also working to address menstrual poverty.

According to the Journal of Global Health Reports, menstrual poverty [or period poverty] is “a lack of access to menstrual products, hygiene facilities, waste management, and education.” To alleviate period poverty in Brazil, Giacomin and her team worked with a group of about 100 women to educate the community about menstruation and their bodies.

“These women receive guidance from prosecutors, lawyers, specialists in women’s health, ecologists, in addition to participating in conversation circles, with topics such as domestic violence, psychological violence, the “Maria da Penha” law, women’s health, environment and sustainability, between others,” Giacomin explained.

Despite all of the work they’ve done, Giacomin’s team still acknowledges that they’re unable to initiate widespread change without the help of the Brazilian government.

“We know that solving a problem like this goes far beyond our capacity. It is something that must be initiated through public policies proposed by the government; however, we have been looking for ways to minimize the scenario in which we are faced,” Giacomin said.

Since working with Dignidade Para Elas, one of Giacomin’s greatest achievements is the knowledge that she’s been able to impact women’s daily lives in a radical way.

I will always argue that this is my greatest achievement: the fact that someone will be helped — Cecília Giacomin

“Since it all started, my motivation has always emerged in the thought that someone could be helped through my project,” Giacomin continued. “This was something that guided me, and that I will always carry with me, but the moment I actually felt this was when one of the women watched by the program called us to tell her story. She told us about what had gone through during her 25-year marriage, which had finally ended through the help of volunteers we presented in our project.”

For Giacomin, these kinds of personal connections with the women in her community are her priority.

“I will always argue that this is my greatest achievement,” said Giacomin. “The fact that someone will be helped.”