Editor’s Note: This story is part of the Global Ties Kalamazoo series published by Knight Life News. From Feb. 12-16, related content can be found on our website, Instagram and Facebook.

Editor’s Note: This story is part of the Global Ties Kalamazoo series published by Knight Life News. From Feb. 12-16, related content can be found on our website, Instagram and Facebook.

Think of a problem you have noticed with schools in this country. Maybe an issue with educational funding comes to mind, and you curse the government for not allocating more money to schools. Perhaps you thought of the disparities between public and private institutions, or even how the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic affected your education.

For an American student at Loy Norrix, these issues are probably not given a lot of focus. But for countless high school students in Brazil, these are not just occasional thoughts, these are huge problems that affect not just education, but the welfare of the country as a whole.

According to Human Rights Watch, the Brazilian government under former president Jair Bolsonaro spent only 32.5 billion of its 48.2 billion Real (R$) education budget in the year 2020. The Real (R$) is the currency of Brazil. One R$ is equivalent to 20 US cents. The Brazilian government also blocked funds from the Connected Education program – an initiative that provides Internet access for public school students.

High investment in both of these things would have helped Brazil’s schools weather the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the government blocked 2.7 billion R$ (over 5.4 million U.S. dollars) in funding from schools the following year in 2021.

In response to the pandemic’s impact around the world, particularly in large developing nations like Brazil, the United Nations warned that “higher dropout rates will have long-term effects on children and on the economy, resulting in lower wages and a reduced quality of life.”

This effect was visible in Brazil where over four million children completely lost access to their education in 2020 despite being enrolled in schools, while many other students chose to drop out.

The shockwaves of these events still linger in the nation’s educational system, having exacerbated many existing problems, such as funding issues and wealth inequality, in addition to the new ones resulting from the Bolsonaro administration and the COVID crisis.

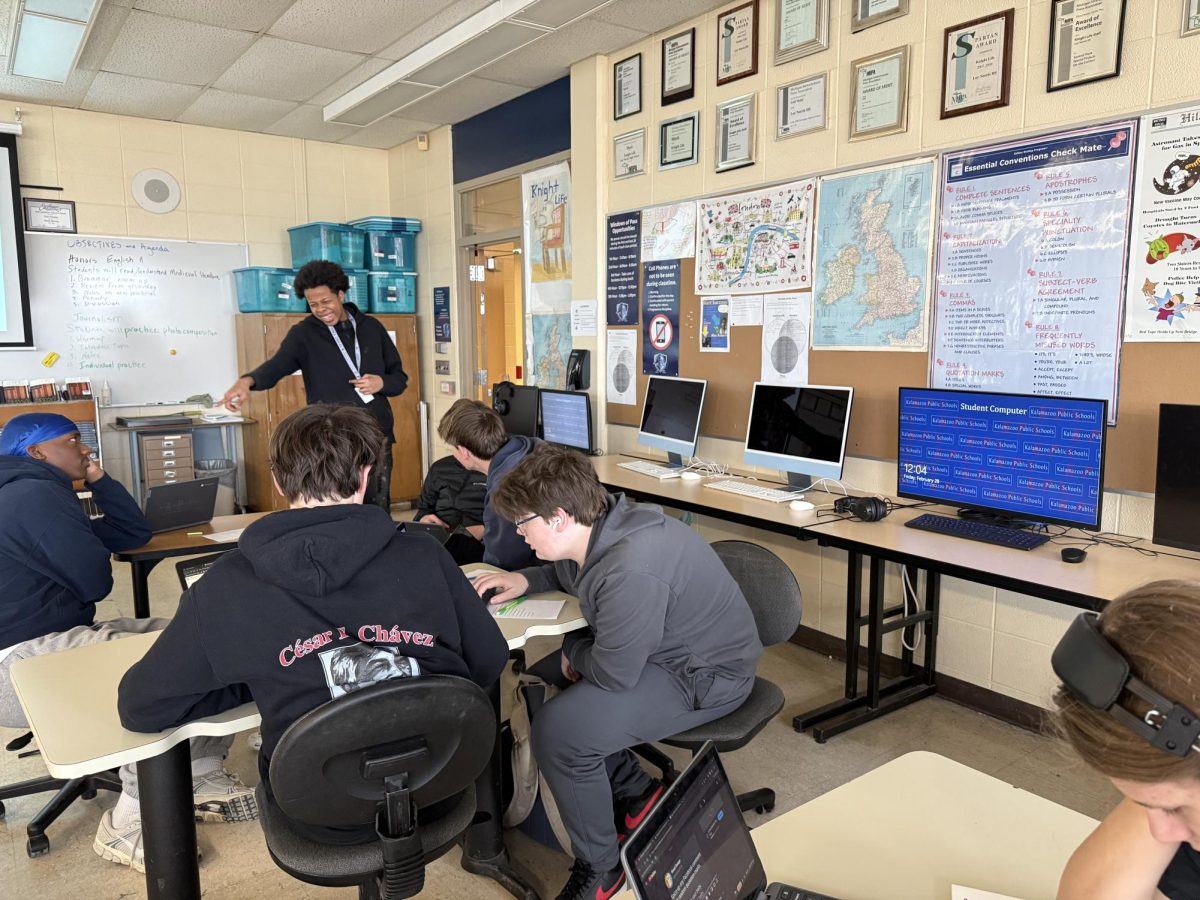

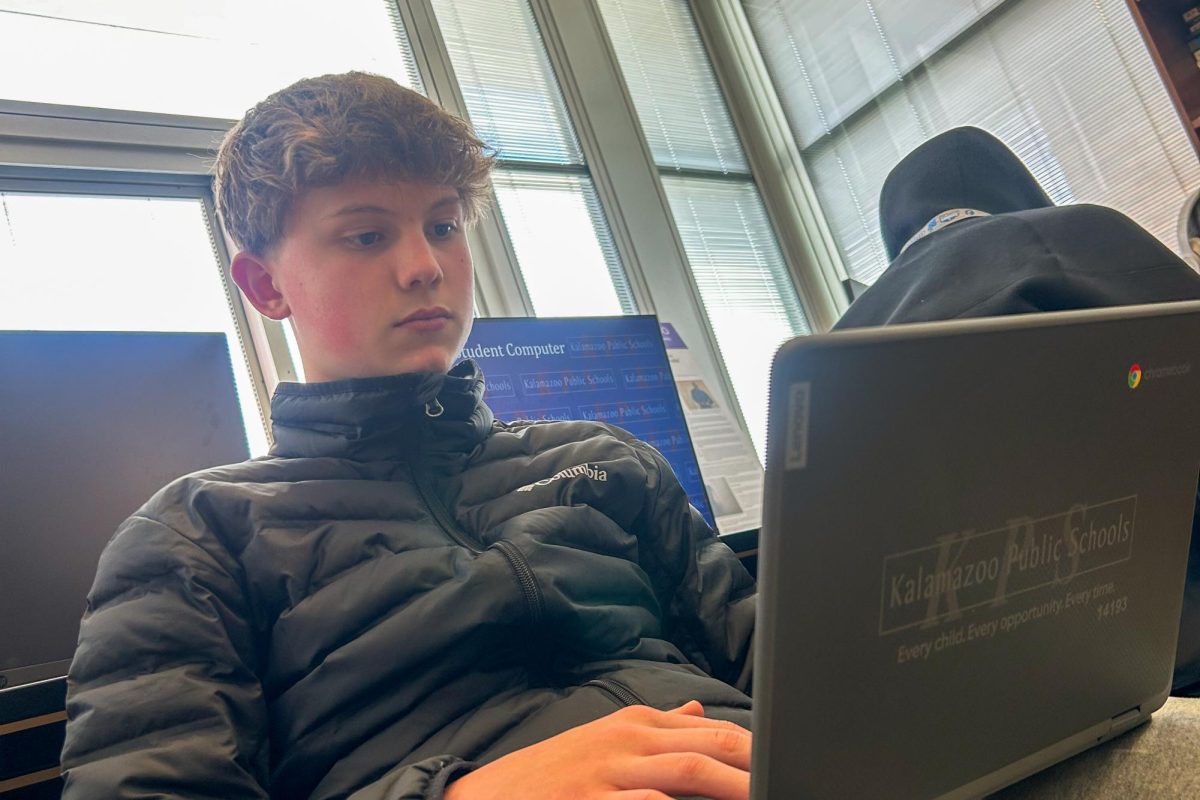

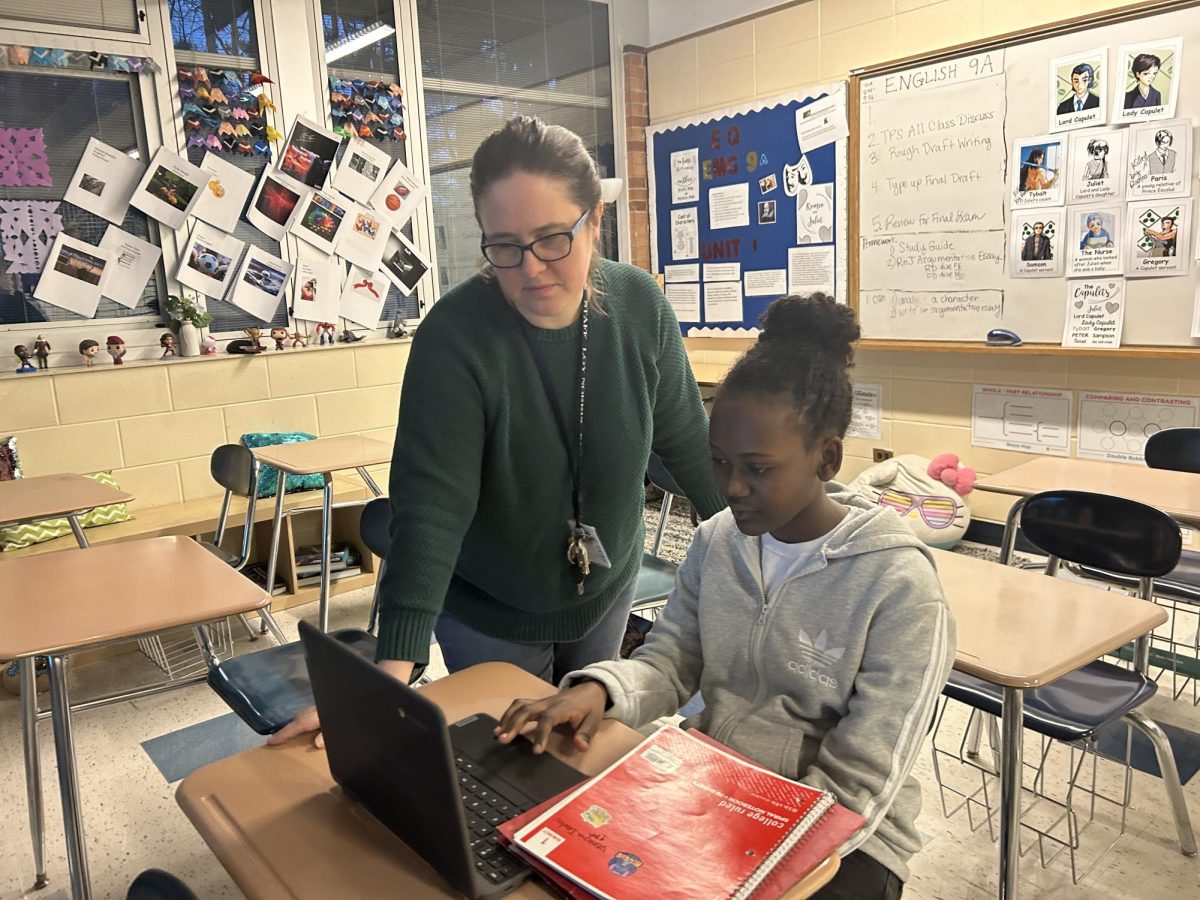

In their recent visit to Loy Norrix, Brazilian Global Ties Kzoo Student Ambassadors shared their own perspectives on the Brazilian education system.

Many students complained about what is essentially the Brazilian equivalent to the SAT: the Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (High School National Exam), or ENEM for short. SAT submissions for college in the US relaxed after COVID-19, but the ENEM is still essential to Brazilian college admissions.

The ENEM is a large, non-mandatory test that is meant to evaluate a high school student’s knowledge of what they have learned. Many colleges in Brazil use this exam in their admission process. Considering how important it is, it is worrisome that many Brazilian students have found issues with this exam. An essay and 180 multiple choice questions are split into two days. The main topics covered are language, math, natural science and humanities.

“We don’t learn everything that is requested, and the things we ‘learn’ are usually just memorized,” said Global Ties Kalamazoo Student Ambassador Rick Robert Tomaz Rezende.

Students aren’t actually retaining the information that is required for this exam because it’s not what they learned in school. ENEM does not give an accurate representation of a student’s skills because the exam content doesn’t reflect real-life schooling. Brazilian students just memorize, take the test and move on.

Another major problem brought up was the social hierarchy in Brazilian education. There are major discrepancies between public schools and private schools. Brazilian public school students have very few choices over which classes they take, and have very few resources compared to private school students.

“I think that private schools are way better in structure and quality education,” said Maria Eduarda de Souza Mendes, another Global Ties Kzoo student ambassador. “They prepare us to ENEM and college since the third grade. Contrary to that, some public schools don’t even have teachers for months. Me, for example, I had no literature and Portuguese classes for almost four months. Some teachers don’t even know what they’re teaching.”

Other students have had different experiences with public school education. Maria Eduarda de Aguiar Silva, another Global Ties Kzoo student ambassador, said that her school has resources like university entrance exam preparation classes and mental health lessons.

“In Brazil, it really depends. Sometimes private education may even be better, but in many cases public education surpasses it,” said Maria Eduarda de Aguiar Silva. “Public schools have much more research opportunities and scholarships to stay in college, but they are heavily neglected by the government.”

Private schools can be very expensive and because of the large class divide, affording a private education for one’s children can be almost impossible. According to The World Bank, in Brazil, the “income share of the richest 20 percent of the population [is] equal to 33 times the corresponding share of the poorest 20%.”

This social divide makes it so that the Brazilian upper class has access to good education and, therefore, opportunities to succeed, while the lower classes are put in subpar schools, creating larger obstacles to success and economic prosperity.

“In my opinion, private education should not exist. Education must not be a product: it is a right,” said Rick.

There are also many problems with the infrastructure of schools in Brazil. According to Associated Press News, “more than 5,800 schools had no water supply in 2017, nearly 5,000 had no electricity and 8,400 had no sewage.” The student ambassadors supported this fact, sharing that many of their schools were lacking in resources and safety.

“My school has many issues, like problems with electricity, bad structure – many classes don’t have air conditioning – and safety,” said Maria Eduarda de Aguiar Silva.

It’s not just the resources that are lacking in Brazil’s public schools: the educational content also has its share of problems. According to OECD Ilibrary, “Half of the 15-year-olds in Brazil lack a baseline level of proficiency in reading,” Additionally, students are frequently not taught strategies to support mental, physical and social health, which can further decrease their capacity to learn.

These problems are often caused by a lack of funds, and in turn, financial shortages are often caused by corruption. A 2012 paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research found not only that corruption was present in the educational systems of many Brazilian municipalities, but also that high levels of corruption were strongly correlated with a diminished quality of learning.

This lack of funding also causes much of the financial responsibilities to fall on teachers and students, causing them to be forced to pay for necessary things.

“In my school, students need to pay 40 cents for every page in almost every test because the teacher needs to print the pages in the school’s printer that is not free. Therefore, the governmental lack of investment is something that affects everything in my school and in the education system as a whole,” said Rick.

This is not to say that everything is bad. According to OECD Ilibrary, “Early childhood education and care has been expanded, enrollment in primary education is close to universal, and around 80% of the cohort participate in lower secondary education, with well over half now progressing to upper secondary education.”

Despite these major improvements, attainment and participation is still behind the OECD average, and many students still struggle to access and stay in education.

With corrupt governments, it is essential that the public rally for change. There are many passionate and informed young students in Brazil who want to make change.

“What is required is an improvement of the educational system and higher investments in public schools, which is — at least in Brazil — denied due to the corruption and collaboration between politicians and capitalists of the private educational area. Education, health, security, water and other basic rights must be free and high quality,” said Rick.