You’re walking down the crowded halls of Loy Norrix, pushing past various students to get to your class on time. You hear another student shout your name, but all you can notice is that amid their sentence, they called you the wrong gender, making your heart sink to your stomach.

Transgender and gender-nonconforming students go through similar experiences daily, regularly being misgendered because of assumptions and mistakes made by other students and staff. Misgendering is rapidly becoming a greater issue as the percentage of gender-diverse students is growing.

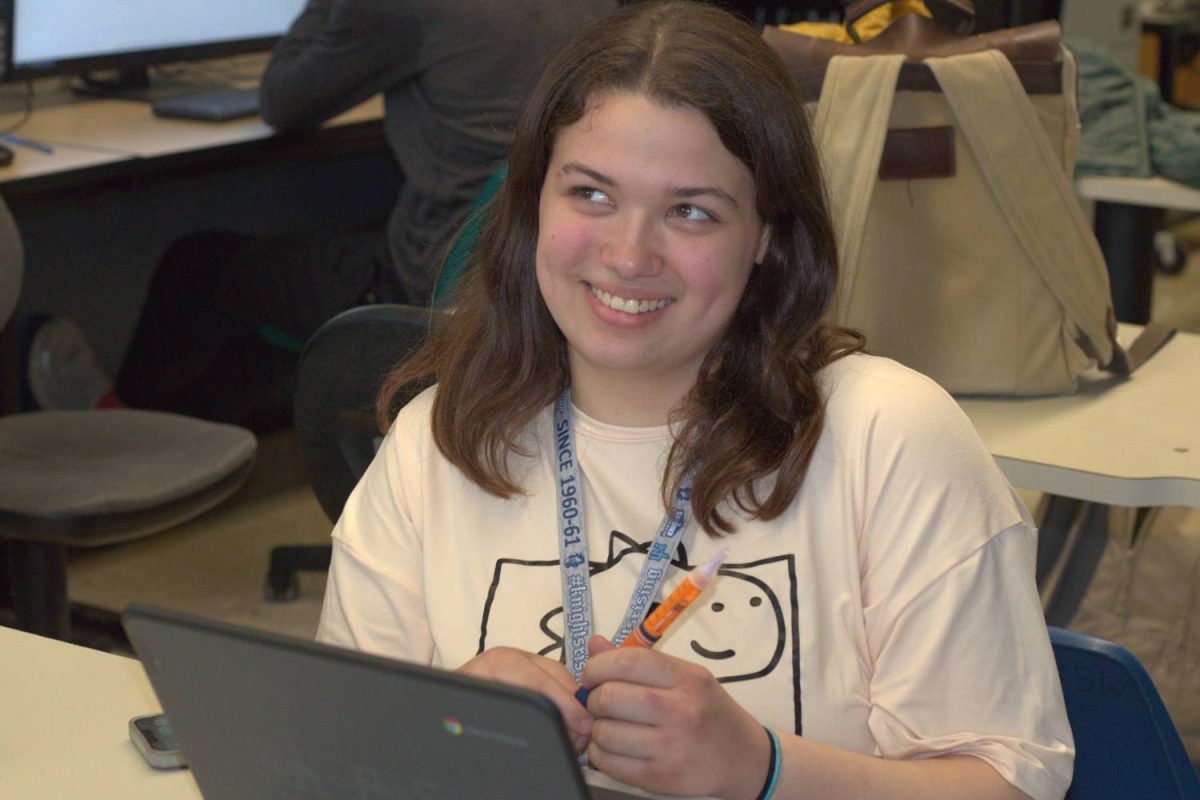

“I came out when I was nine or ten years old,” said junior Jazz Coston. “I kind of just told people, ‘I’m trans, I’m non-binary.’”

Coston said their family is supportive of them as they’re figuring out their identity, but they don’t always feel comfortable around their peers.

Coston reported that, on average, they are misgendered more than ten times on any given day at school, which means they’ve had to get used to people referring to them using gendered terms they don’t identify with.

“I found myself having to explain what non-binary means,” said Coston, “and that I’m still non-binary, despite the fact I present femininely.”

In a survey of 28 transgender Loy Norrix students, 61% said they are misgendered five or more times a day. Over 44% of the respondents said other students are more likely than teachers to misgender them, and another 37% said teachers and students are equally likely to misgender them. This suggests that, more often than not, transgender students are misgendered by their classmates.

Only 15% of respondents said that they don’t get misgendered at all, and all of those students are medically transitioning. This means they’ve taken medical measures as a part of their transition, which can include hormone replacement therapy, hormone or puberty blockers, and similar measures. Though, 23% of surveyees, including Coston, said they don’t want to medically transition.

“Medically transitioning isn’t everyone’s end goal,” Coston said.

As a response to being surveyed, Coston answered that they prefer to present femininely, and they don’t plan on medically transitioning. They like their appearance now, which makes them more prone to misgendering.

Similarly, sophomore Ash Ferguson finds that students will often second-guess their assumptions.

“Someone will use my correct pronouns, and then the person next to them will be like ‘that’s a girl,’” Ferguson explained. “Or like, ‘is that a ‘she,’ a ‘they,’ or an ‘it’?’”

Purposefully making fun of a non-binary person like this is incredibly hurtful. The question, and any others like it, are dehumanizing and reduces trans people to a stereotype. Not only is it presumptuous, but it also highlights a social stigma that transgender and gender non-conforming people have to fight just to live their lives in full.

Ferguson is often misgendered, like many trans students. Misgendering isn’t completely avoidable, which is something many teachers have to face in their classrooms. Spanish teacher Kristin Antoniotti tries her best to correct herself when she accidentally uses a student’s wrong pronouns.

“I would hope that I just say ‘sorry,’ correct what I said, and just keep it moving, like not make it a huge deal,” Antoniotti said. “I don’t know if I shoot 100% in that regard.”

Fortunately, for these students, there is a way for trans students to reduce misgendering. Coston and Ferguson, along with 54% of survey respondents, have changed their names in the school system, altering what teachers and students see in PowerSchool and Google Classroom.

“It was a nightmare before I changed it [Coston’s name] in the system,” Coston said, “because then when you have a sub, then you’ve got to be like, ‘oh it’s actually this name’ and the horrors of having everyone hear your deadname is not fun.”

While they have a way to change their names in the school system, it’s much harder for students without families supportive of their trans identity, because the state requires parent or guardian signatures to consent to legally change the names of minors.

“If a student doesn’t have adults in their life who are accepting of their new name,” said Antoniotti, “then that means they would have to come to school and be retraumatized by people using the name that they don’t identify with.”

Antoniotti wasn’t aware of this policy beforehand, given that only a small percentage of her students are transgender.

“I also wish we lived in a world where youth can say ‘this is my name’ and there aren’t so many hoops to jump through to get there,” Antoniotti said. “I’m thinking about what coming out to my family was like, I’m thinking about this as a parent, a teacher, and a student.”

Math teacher Rosemary Sidwell, as well as many other teachers, have solutions. At the beginning of every trimester, Sidwell has all her students write their preferred names on notecards, which Sidwell refers to when addressing her students. Sidwell does this for her transgender students, but she also finds it to be important for cisgender students as well.

“Even if it’s not like they have a deadname, even if they just don’t like their full name, and they’d just rather go by ‘Alex’ than ‘Alexander,’” Sidwell continued. “You [teachers] should be making those efforts in the first week, so they are comfortable, so that it’s not setting you up for failure, so you don’t have to have that conversation seven weeks in when they’re struggling to do anything. Then you’re like, ‘oh my god what’s wrong?’ and they’re like ‘well, you don’t call me the right name.’ That’s an awkward conversation to have seven weeks in.”

Similarly, Antoniotti has her students fill out sheets that include their preferred names, as she feels that students shouldn’t have to stress about telling five new teachers every trimester about their preferred names.

“I would hope more teachers would ask questions at the beginning of the trimester,” Antoniotti said. “Even if it’s just on a piece of paper, versus putting it on the students, because I feel like that’s just a lot for students to worry about.”

Sidwell has the idea to edit attendance sheets in PowerSchool, changing students’ names so when substitute teachers come in class, students don’t have to brace themselves for their dead name being called out.

“To be able to say [in PowerSchool], ‘no that’s not Joe, that’s Lex,’ or something like that, that would be awesome,” said Sidwell.

She also suggested training all teachers, especially substitute teachers, to take attendance by looking at the pictures on the seating chart, rather than the names that may be incorrect.

“Most subs know by now not to just start calling out people’s names, because many subs can’t pronounce them anyway, so it’s not helpful,” said Sidwell. “I use the photos in PowerSchool to make sure they’re in their assigned seats, basically.”

Sidwell and Antoniotti agreed that about three to five percent of their students identify as anything other than cisgender, but Antoniotti added that the number of trans people in her classes is steadily increasing.

“I think with each passing year, there are more people whose identities fall outside of the binary, and it’s just talked about more,” Antoniotti said. “It’s more understood.”

To take steps to further support transgender and gender-nonconforming students, the administration can take action to ensure a safe, respectful, and welcoming environment for all students alike.

Cottie • Nov 22, 2024 at 11:10 am

Important stuff. Thanks for teaching people, Knight Life.