“A lot more people are just like, ‘both sides suck. Nobody represents me,'” said history teacher James Johnson, describing the current political culture of the youth vote.

This sentiment summarizes a growing problem with young people across the country: the feeling of political apathy. Especially as the 2024 presidential election draws near, young people are finding it increasingly difficult to summon enough energy to care about their government and the politicians who are supposed to represent them.

Junior Bjorn Nelson has been a part of the YMCA Michigan Youth in Government for two years. His first year, he participated in the program as a lobbyist, and this year, he leads one of the Model Judiciary Program (MJP) teams. During this time, he’s observed the political apathy plaguing the American political culture.

“It’s a culture that essentially has stopped caring about what’s happening with the political process because a) it is no longer having a meaningful effect on people, b) they don’t feel like they’re having an effect on the process, or c) the process has become so obscured by the way we report on things, and the sheer amount of stuff happening that it’s gotten to a point where people can’t keep up,” observed Nelson. “And once you can’t keep up, you give up on it.”

No matter the reason behind current participation rates, it’s clear that young people haven’t historically been politically active.

According to the Harvard Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics, “less than half of young Americans vote, even in presidential elections, and just 10 percent of Americans between 18 and 24 met a standard of ‘informed engagement’ in the 2012 presidential election cycle.”

This pattern continues at Loy Norrix as well. A voluntary survey of over 200 students showed that although over 20% of the students who responded were eligible to vote, only 3.2% of respondents indicated that they’d voted in Michigan primaries.

As Nelson sees it, even if young people were to go out to the polls and cast their votes, as some did in the Michigan primaries, the youth vote wouldn’t be as influential as it is often romanticized to be.

“It’s basically the same as voting for a third-party candidate in an election or anything like that,” said Nelson. “Your vote is essentially wasted, but you’re doing it to send a message. And that’s essentially all that youth can do: go out there, spread their message, and hope that politicians recognize that, at some point, we will be their constituents and at some point we will be important to them, and the youth vote will eventually matter.”

Nelson points to one of the major pitfalls of the current political culture in the US: historically, voters above age 60 make up the largest percentage of those who participate in presidential elections. According to the United States Elections Project, the data of which is summarized by Our World In Data, while 60+ year olds have consistently voted at rates around 60-70%, participation by 18-29 year olds hasn’t ever cleared the 50% mark between 1988 and 2016.

According to history teacher Matthew Porco, this trend isn’t going to change any time soon.

“As far as influencing politics, I don’t see a lot of policy directed towards young peoples’ concerns,” said Porco. “It’s doable, but outside of Bernie a couple times, there’s no discussion about that. Almost everything our government does is directed towards old people.”

As Porco points out, low youth participation creates a vicious cycle for young voters. Young people don’t vote, so politicians don’t address issues important to them, so young people don’t bother voting: the cycle repeats.

Although youth political participation is low, studies have shown that access to civics, social studies and government classes makes for a more informed youth electorate.

Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, better known as CIRCLE, is one of the most thorough research centers for political and civic engagement. Their goal is, through extensive research and studies, to analyze and advance youth political engagement.

As CIRCLE puts it: “A strong, equitable civic education is the foundation of a strong democracy, which requires a citizenry that has the knowledge, skills, and desire to participate in it. That’s always been true; it’s even more so now, at a time when the country is deeply polarized and its people are poorly trained to meet the modern challenges of our political system and our civic life.”

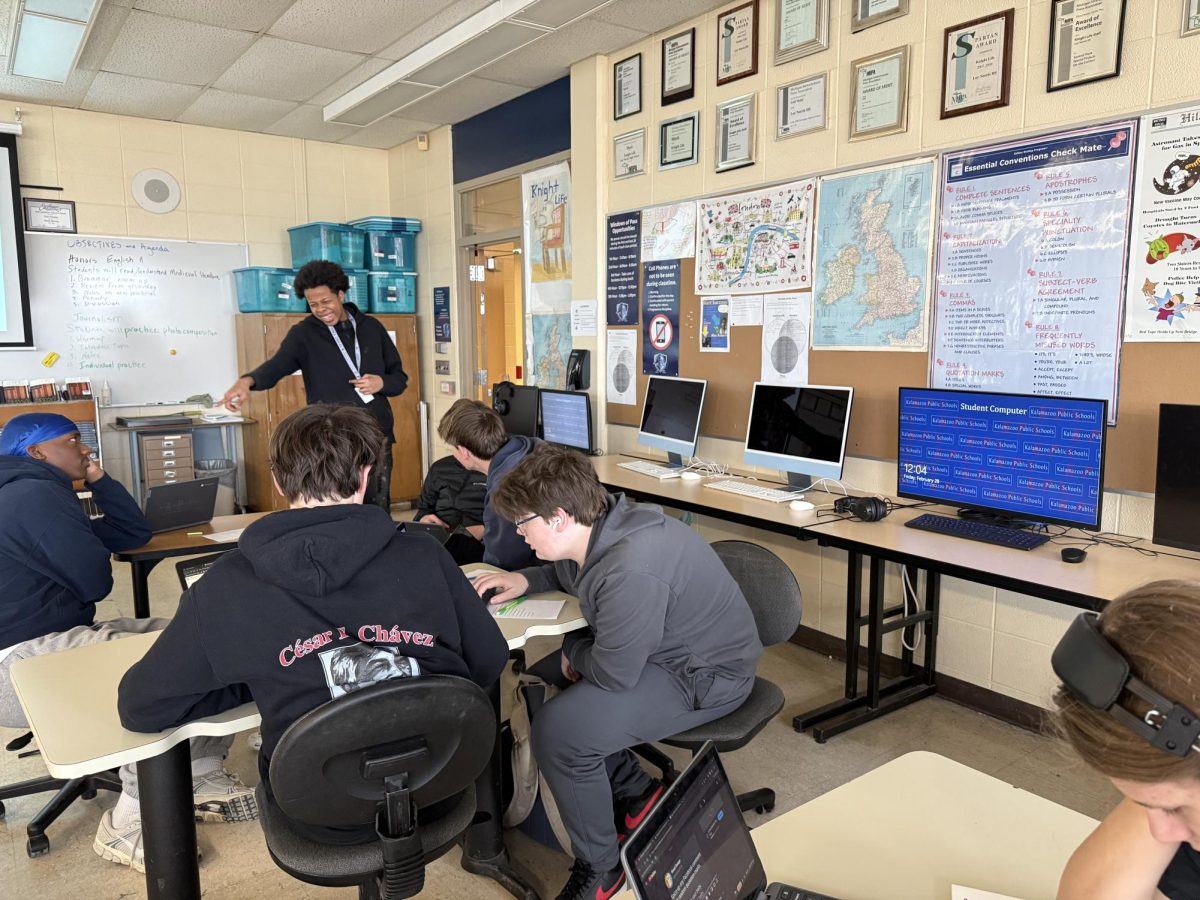

This principle holds true at Norrix as well, where social studies teachers work hard to make sure that their students are educated about their government.

“I try to make it very clear that I’m an active participant and that I do vote,” government teacher Kyle Shack said. “It creates that norm that this is a thing we all participate in.”

When approaching the subjects of politics in class, however, teachers can find themselves trying to strike a balance between sharing too little and too much of their own beliefs.

“Kind of like celebrities: when a celebrity takes a position, they’re going to alienate half of their audience,” said AP Government teacher Michael Wright. “I think if you’re a teacher, you’re going to do the same thing. You’re going to always alienate a particular part of your audience and then from thereon, people are going to question everything you have to say, regardless of how much you believe it to be true or how many actual facts you can provide.”

Johnson also believes that this polarizing aspect of politics makes it difficult for students to participate politically.

“The way our elections, especially our federal elections, are run is very team-oriented… It’s like the good guys versus the bad: it’s the in group versus the out,” said Johnson. “And if they don’t feel like they’re a part of the team, either team, then there’s just not much motivation to be informed about what’s going on or to show up from the day they’re 18 and be part of the process.”

For these reasons, teachers like Wright, Shack and Johnson focus on not revealing their political stances during class. However, fellow history teacher Matthew Porco has become more candid with his students as the years go on.

“I’ve found that, in what we’ll call the ‘Age of Trump,’ I’m a lot more open,” Porco said. “I don’t try to convince anyone that I’m right.”

While teachers stay away from sharing political beliefs in class, and young people aren’t politically engaged, politics still infiltrates many of their lives.

Recently, the conflict in Gaza between Israel and Hamas has encouraged a large coalition of American Youth to begin paying more attention to their government. As CIRCLE points out, “about half of young people say they’re paying some or a lot of attention to the conflict between Israel and Palestine,” and significant proportions of young voters ages 18-29, up to 82%, according to a January Economist poll, ranked foreign policy as one of their most important issues. These patterns continue on college campuses like Columbia and the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), where protesting students are calling for a ceasefire in Gaza as they face resistance from police forces.

The recent pattern of youth motivation in foreign policy is repeated at Norrix. Although it wasn’t the top choice, over 47% of the students surveyed indicated foreign policy and human rights violations as being most important for presidential candidates to address, second only to taxes and inflation (50.5%), with one surveyed student neglecting all other issues and submitting “ceasefire in Gaza” to the “other” option.

According to Porco, the recent interest in issues abroad by young people has been fueled primarily by the internet.

“If you look at young people’s engagement with, say, what’s going on with Israel and Gaza right now, I think it’s fueled a lot by social media,” said Porco.

The internet does serve an important role in making international events accessible to American teenagers. The onslaught of horrific news and gory imagery, however, also might desensitize voters, making them less likely to feel outrage that will drive them to the polls, as Shack points out.

“For anyone on it [social media], I think the political impact also can be kind of a flattening effect… if everything is presented in that same medium, if it’s like, war in Gaza, puppies, war in Gaza, that you’re just scrolling through, I think it’s hard for some people to gauge ‘what are the things that are having the most significant impact?’ or ‘what are the things that are just being presented?'” said Shack.

Shack points to an issue that Nelson brought up: when young people are overwhelmed by the amount of information presented to them, which is especially likely to occur through social media, they tend to disengage from news and politics completely.

Since 71% of Knight Life survey respondents indicated that they obtained news and information from social media, this could have a major impact on their generally dispassionate outlook on American politics.

However, the flattening effect that Shack describes isn’t the only effect of social media on news consumption: the infamous echo chamber is also formed by this form of consumption.

“It’s called the echo chamber, where it’s just reciting what you want to hear because that’s what the algorithms know will keep your attention on these apps,” said Johnson. “I think the effect that has on the political culture for young people is that it’s going to lead to even more polarization, I fear, because people are just going to be living in this on-demand, catered world. It’s fake.”

As Johnson points out, social media users often fall victim to confirmation bias, which traps them into echo chambers in which they’re only consuming news written with a specific ideology in mind. The hazard there is that they will fall victim to fake news or rely more on short snippets of information rather than taking the time to read in-depth news, which has only become more accessible with platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

Despite these echo chambers, according to the same student survey, 35% of the respondents marked themselves as moderate on the political spectrum. This shows that many young voters are not necessarily attracted to candidates based solely on their political party. Instead, these young people may instead only look at a candidate’s public persona or their views on singular issues in order to make a more informed decision.

In the age of internet news, making an effort to utilize reliable and unbiased news sources is important, and students and teachers alike have found sources they trust.

Wright suggests Real Clear Politics, a news website that describes themselves as being free of affiliation to a particular political party or ideology.

“They will pull a source that’s slightly to the right and a source that’s slightly to the left, and they’ll post them together,” Wright said.

The other popular sources for teachers were NowKalamazoo and MLive to stay updated on local news, and common sites like CNN, the New York Times and the Washington Post for national or international coverage.

For students, 64% of those students surveyed do read online news sources. However, the extent of their media literacy and understanding of bias tends to vary. For students who are interested in politics like Nelson, reading articles from far right and far left sources is a method that helps him understand the nuances and differing perspectives within the news.

“I think that’s the important thing, to keep your mind open,” Nelson said. “Even if this news source is biased, they might be correct in this article.”

While the current state of American politics can be depressing, it is incredibly valuable for students and young voters to stay active in the news and educate themselves on what’s happening in their world. Voting can be a tool to endorse a particular candidate, fight for a specific issue, or make a statement.

If you are interested in registering to vote or are curious about when the next election will be, the Michigan Department of State provides all of this information.