It’s Time to Change the Way We Teach Math

May 31, 2019

If you are afraid of math and hate the subject, if you panic on tests or blank out and forget what you have studied, you’re definitely not alone.

According to the University of Nebraska, math anxiety affects more than 50 percent of the U.S. population. Students associate math with frustration and failure. For this reason, the United States performed below average in math in the results from Programme for International Student Assesment of 2012, ranking 27th among 34 other countries participating in analysis by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Loy Norrix is not an exception. U.S. News statistics show that at our school mathematics proficiency is around 30 percent, while reading aptitude is more than 60 percent. Students no longer feel motivated to do math because routine practice and memorization of algorithms which according to the United Federation of Teachers interferes with a real understanding of mathematical concepts.

“It depends on the teacher,” said sophomore Claudia Ligman when asked how she feels about math. “Some teachers make it easier for me to understand math than others.”

Jo Boaler, math professor at the University of Stanford, claims that the way we teach math contains too much methodology and calculation and not enough real understanding of the problems we are given. Students often find themselves incapable of comprehending math classes. Boaler also remarks that homework and quizzes are part of the problem, and not a solution.

The problem begins with homework and its negative effects on students. When asked about homework, Nancy Kalish, author of “The Case Against Homework: How Homework is Hurting Our Children and What We Can Do About It,” says that many homework assignments are “simply busy work” that makes learning “a chore rather than a positive, constructive experience.”

Students, parents and experts worry about homework, specifically busy work assignments because long sheets of repetitive math problems tend to make children dislike school.

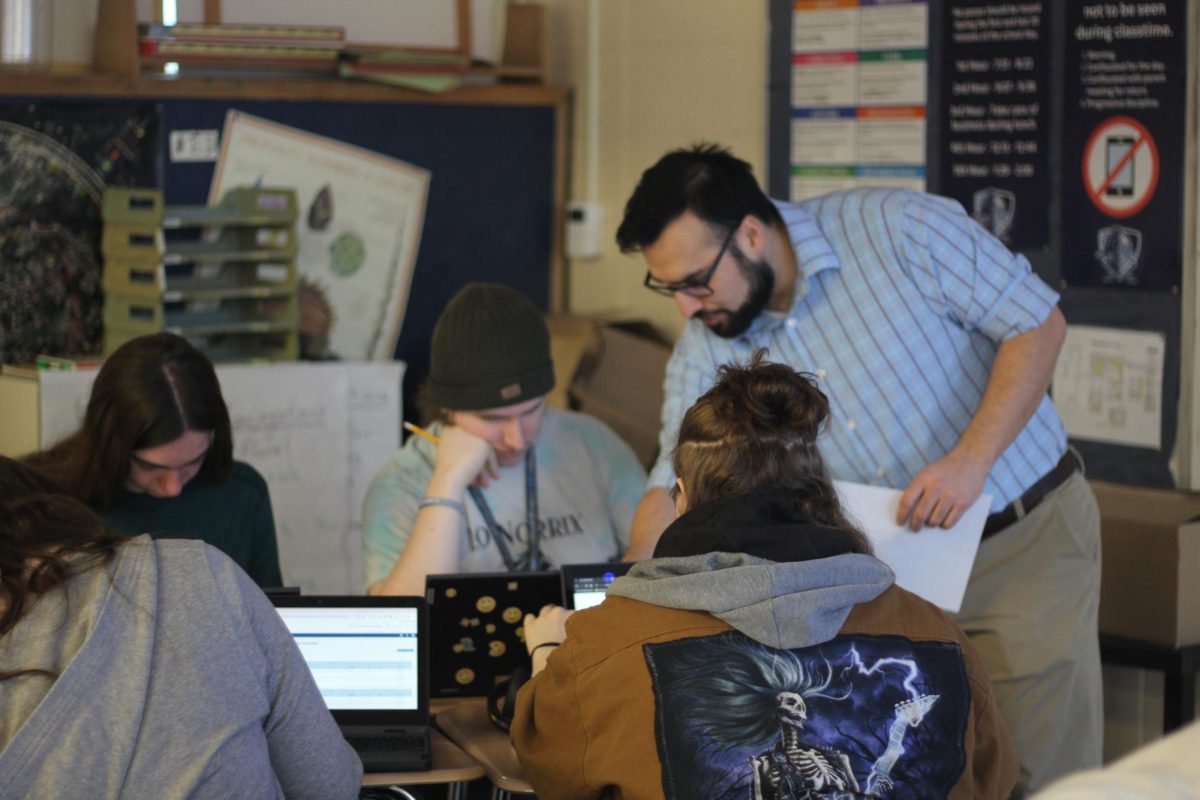

“I think kids don’t like math because they don’t see the value in it,” said Dyami Hernandez, math teacher at Norrix. “For me, it’s always been really difficult at a high school level to make students like math because at this level they already have an opinion towards math and they know if they’re good or bad at it. I always try to take the students who struggle and show them that they can be successful even though they’ve failed in the past.”

The way in which we grade students doesn’t seem to work either. Tests and exams are an inaccurate representation of knowledge and failure is a critical point. An article from Psychology Today explains that teens tend to have a negative mindset about themselves and failing tests can make them feel incompetent.

Students are likely to fail math because of how the tests and exams work and affect their grades. Boaler claims that students do poorly on math exams because they need time to think and solve the problems and feeling like they’re going to run out of time will limit their math skills.

A student could be very smart as well as a hard worker, but they could also be bad at taking tests. The test is therefore unfair because it may not accurately portray students’ abilities. When a certain class becomes the subject of constant failure, which usually happens with math, students end up hating the class and eventually giving up.

Tests and exams might still be necessary to assess students, but instead of just having long homework assignments, teachers should give students real-life problems in class where they would have to apply what they’ve learned. Giving students a creative, realistic way of using the knowledge from the class would make it easier for students to completely understand the concepts and, consequently, they wouldn’t get bored and frustrated with math and they’d do better in exams.

“It feels really good when you get the problem right but I personally don’t like math because I don’t find it interesting,” said sophomore Ellie Lepley.

The traditional ways in which we teach math are perceived by some people as too boring and don’t let students be engaged in the process of learning. We need to end the frustration and fear that many students feel towards the subject and transform math into an appealing and useful class.

dolphinwrite • Jun 1, 2019 at 6:47 pm

There a many who have taught math with great success over the years. Some of my math teachers had a knack, though most I just had to grind as with my classmates. But I want to reiterate this idea of the math brain versus the language, whether I am penning this correctly. When you look at a puzzle, but not involved, simply looking at it until it makes sense (Could be figuring out a light switch, watching a bird find a worm, then the Ah Hahh moment. It’s that way with math: always. You listen to the lecture, take notes, but then look at the problem as if from a distance until it starts to make sense. During my second time through college, I did this with all of my professors. I didn’t try to learn them. I listened, and as from a distance, I observed both them and what they were saying. Very quickly, in all of the lectures, I knew where they were coming from. I did this with a horse, having never trained one, and trained it. I watched the horse. It gave me signs. Now, I understand for many they don’t “see” what I’m saying (And there are those who learn by a different modality.). But with all of my students, even the ones who went back to using their own methods successfully, when they tried this, it worked. It works because it’s so simple. Just observe. Watch. Listen. Wait. Once you “see” what the problem is telling, the rest are easier because you’re getting used to that part of your brain.

Learnography • Jun 1, 2019 at 6:39 am

It’s good writing ! Many students dislike mathematics.. This is the subject of problem solving activities and it requires the practice of intuitive knowledge. The dimensions of knowledge transfer can make maths learning comfortable in the classroom.

In fact, maths learning is similar to the learning transfer of bike riding. Teaching is not necessary in bike learning but motor science of the brain circuits is required in bike riding. Teaching system makes maths chapter difficult in the learning transfer to student’s brain. Maths learning becomes very easy in the classroom when students apply the dimensions of knowledge transfer in brainpage making process. Thanks

dolphinwrite • May 31, 2019 at 5:03 pm

Wow! This is a subject I’ve worked on in helping many others. Thankfully, I learned the importance of understanding. I was always pretty good at math, but I think that was in part to both determination and enjoyment of the subject. *On my site, I wrote about not doing well in school. I went onto a university, but dropped out, though I did well through gritting my teeth. However, as I worked several jobs, I started looking at things differently. Eventually, I returned to the university (Always finish what you start. That sort of thing.). It was there that I realized something. I knew I couldn’t do the 20 hour study per week thing anymore. I didn’t have the patience. But I started piecing things together, finding my own way to learn. **Here’s something I’ve shared with others who struggled in math. First, I explained, it’s important to have your basic facts in mastery. After that, just listen to me when I explain math problems. Afterwards, as you look at problems, pretend there’s distance between you and the problem. Look at them as if you were looking at a piece of machinery, or puzzle, “looking” to see and understand what you are looking at. For those students who took this to heart, their grades rose, some even way up. One young lady went from struggling to garnering A’s each quarter. **Did I do anything? No. She did it. She found that space inside her mind where she could understand anything.