As crises increase in high schools, more emphasis to be placed in Student Resource Officers, despite objections to police in schools

How SROs can serve to reduce crime and reduce budgetary strain in police departments

Credit: Elias Nagel-Bennett

Officer Epps in the tower during passing time. While the SRO is often a last resort in student discipline, Epps is the first line of defense against intruders entering the school.

February 17, 2022

The hallway is abuzz with the clamor of feet, shouts and greetings, and the twisting and turning bodies of students, with dozens of destinations and paths in mind. To keep some sense of order, Loy Norrix employs 6 campus safety officers and a school resource officer, known as an SRO.

Norrix’s SRO, Eric Epps, has been put in the school with a focus on protecting the student body from situations similar to those that have been unfolding across the nation in recent years, such as the shootings at Oxford, Michigan, and Parkland, Florida. SROs are also tasked with improving the relationship between police and students.

A key part of both SRO training and a broader initiative within the Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety (KDPS) is the Group Violence Intervention (GVI) program, a new focus for SROs in high schools. GVI aims to discourage gang activities and lower youth homicide by actively engaging with minors both preemptively and remedially.

But GVI is not the full extent of training SROs receive. According to a memorandum between the Kalamazoo Department for Public Safety and Loy Norrix (page 169), SRO training includes Anti-Racism awareness, district-level training deemed necessary by the district chief of security or the school administration, and “supporting all activities deemed necessary by building administrators and the chief of campus security to become fully ingrained in the culture of Kalamazoo Public Schools.”

In a statement on page 164 of the Kalamazoo city commission’s agenda, James K. Ritsema, the City Manager, stated that the SRO program also serves to “Mentor students and help reduce juvenile delinquency, monitor crime statistics and share information with school administration to design crime prevention strategies, maintain visibility and attend school functions as necessary, and be a positive role model for the students and endorse the profession of law enforcement officers,” (City Commission Agenda Report, Item J.1.)

Both from their training and the goals laid out by the police department and city commission, it is clear that the SRO is designed primarily to keep KPS more secure from internal and external threats. At the KDPS, our top priority is keeping this community safe, — Eric Epps

“At the KDPS, our top priority is keeping this community safe,” said Epps. “Members of the Loy Norrix community can feel free to request assistance at any time.”

The problem of youth homicide is closely linked with highschools and in part shows why a police presence will be stationed in Norrix until such a time as the safety provided by their presence is no longer needed.

“Although not unique to Kalamazoo, one recent challenge faced by KDPS and the community as a whole is gun violence. Specifically in Kalamazoo, gun violence has increasingly begun to involve younger citizens,” Epps said.

KDPS has had an officer stationed in Norrix full-time for over a decade now and shows no plans to deviate. Nationally, the SRO program began in Flint, Michigan, with a focus on fostering police-youth relations and engagement in the community. Over time though, SRO programs, especially in Flint, began to focus more on punishment and active investigation, cementing the popular image of SRO’s as normal cops stationed within schools, fueling a school-to-prison pipeline.

The focus of SRO’s in KPS is not towards arrest however, rather the opposite. By utilizing a multi-layered approach to discipline, the number of arrests compared to the number of reports filed is very small, which reduces the total number of police that actually need to be at Norrix. By mitigating the escalation of violence, instances in which additional police resources have to be dispatched to Norrix are far lower than they would be without an SRO, by the estimate of KPS within the same report.

This is not to say that the SRO program is without controversy. In July 2021, the Kalamazoo City Commision voted on a measure to keep the SROs at Norrix and Kalamazoo Central, after a year of lapse due to online schooling. The City Commission has full control over police funding, so when Black Lives Matter protests in Kalamazoo raised the police presence in local schools as an issue, some adjustments were made to the previous program, such as encouraging more interaction between school officials and the officer. This is part of why seniors and juniors may see a difference from the early 2020 school year, with Officer Epps being one of the first people students see in the morning.

“I like them [SROs] personally. They’re our safety, you know? If we don’t have them, who’s gonna protect us when we need it.” Sophomore Aries Hobson continued, “We can’t, we’re sitting ducks.”

When asked about the SRO presence in school, sophomore David Ducket concurred with Hobson. Ducket said, “It doesn’t really bother me. I really think they should be here. There’s fights every day. They need to be prevented.”

Opinions are divided among the student and staff body. Some see the SRO as a net positive, while others would prefer to see the school police-free.

Past actions of Kalamazoo Central students in the summer of 2020 and the January 17th walkout at Norrix have called for a reform or repeal of the SRO system within KPS, while internal administration has remained firm on the viability of the program.

English and public speaking teacher Joe Kitzman has a positive outlook on police officers in school, “It’s nice to have them here.” Kitzman said. “They’re needed in extreme situations, so that fights that could cause harm are resolved without needing to call the police every time.”

How SROs can serve to reduce crime and budgetary strain in police departments

Police officers can be seen everywhere, from patrolling streets on foot and in cars, providing security for public events, actively pursuing criminals or performing a variety of roles in the community. KDPS, or the Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety, is the most visible arm of local government, with 294 full-time employees. In just 2021, they made well over 2 thousand arrests in total.

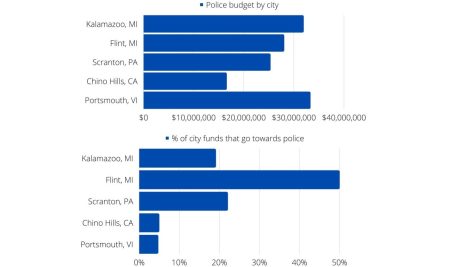

With such a large presence, however, comes a heavy cost. The police department has to operate patrols at all hours of the day, along with maintaining a fleet of vehicles, handle K9 units, upkeep equipment in the field and lab, train bomb disposal and SWAT units, along with a myriad of other operating costs. In total, the KDPS operates with a budget of over 30 million dollars, out of the accumulated city budget of 166 million. At surface value, this seems an immense amount of money, over 19 percent of the total city spending, but in comparison to similarly sized cities, Kalamazoo spends less on its police force.

Scranton, Pennsylvania, spends a cumulative 22% of its budget on the police, with a population only about a thousand people greater than Kalamazoo. On the extreme end of this lies Flint, Michigan, with a total 50 percent of its budget spent on city security. Scranton and Flint have marketbly greater crime rates than Kalamazoo, and an increase in police officers has proven to reduce violent crime.

Compared to Flint, 1 in 79 people in Kalamazoo will be the victim of a violent crime, while 1 in 73 will be victims of a violent crime in Flint. Despite Flint’s police receiving a far larger part of the city’s operating budget, raw resources have not solved the city’s issues with crime.

Therefore, the question must be begged, why does Flint have such diminishing returns on police spending compared to Kalamazoo? Quite simply, reducing crime doesn’t just take more boots on the grounds or more cars roaming the streets, it also means engaging the public, something that starts as early as high school.

Herein lies a significant difference between the Kalamazoo and Flint departments: while Kalamazoo spends over 6 million on its community engagement funds, Flint has no dedicated fund for community engagement listed on their budget. This means that Flint doesn’t have a program similar to Group Violence Intervention (GVI), a program used by KDPS to discourage gang activities through engagement with the community.